ON SUBSTACK: “One of our ideas is just to do crazy things.”

Why we fire a wood-fired ceramics kiln to 2500℉ at a Zen temple

Unloading the first chamber of our wood-fired ceramics kiln.

The 1999 documentary, GENGHIS BLUES, tells the story of the blind blues singer and guitarist Paul Pena as he journeys from San Francisco to a national throat singing competition in

Tuva, a small Russian republic bordering Mongolia. On his trip, the self-taught bluesman turned throat singer samples yak wine, rides horses, and has an existential crisis in which he almost abandons the whole trip. Of course he persists, however, and is treated to a hero's welcome in what the film calls one of the last bastions of true adventure—a place so far off the beaten path that it's somewhere only the most intrepid travelers go.

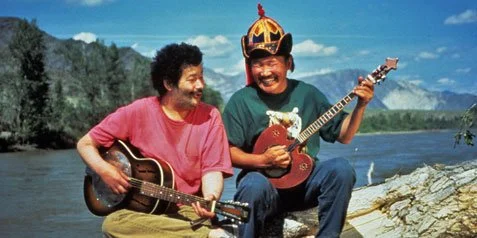

A scene from GENGHIS BLUES

Pena is flanked on his trip by a small crew. He is also aided through funding and introductions by an eclectic and informal group called the Friends of Tuva. Founded by the world renown physicist Richard Feynman, the Friends of Tuva are linked together not only by a fascination with Tuva but also by a shared zeal for uncommon adventure.

“One of our ideas is just to do crazy things," says the group's founder during the film.

This idea of "just doing crazy things" is something we relate to a lot at Chozen-ji, the Rinzai Zen temple in Honolulu where I live. And, in fact, two weeks ago, we did our own sort of crazy thing: we fired our wood-fired ceramics kiln.

Even in the ceramics world, wood firings are not common. Most ceramicists instead enjoy the reliability of a gas-fired kiln. And these days, ceramics programs in schools are even ditching their gas kilns for the staid safety and programmability of electric kilns. It's not hard to understand why. Firing a wood-fired kiln is a risky, even dangerous, endeavor. Most of all, it's kind of a crazy thing to do and a lot of hard work.

Preparation for our firing, which took place May 6 and 7, took approximately nine months. As you may have seen on my social media, I made a lot of ceramics, as did the other Zen priests and students training with me. Month after month, we made pieces, bisque fired them until they were sturdy enough to handle and store, and stockpiled them for a date we had set out months in advance.

Meanwhile, our head priest and a crew of students drove around Oʻahu, chainsaws in hand, picking up fallen trees. They brought the wooden rounds back to the Dojo and fastidiously chopped them into logs and then 1-inch widths of kindling. Having realized a few years back that hydraulic log splitters are a waste of time and money—and a waste of good Zen training —they did all 2 cords with axes. (The Zen of chopping wood deserves its own article, but that's for another day.) Then, for at least six months, the wood had to dry.

By the time May 6 came around, a dozen people had already labored in one way or another to get us ready for the firing. Then, even more troops were called in. 26 Dojo members signed up for firing shifts, 4 to 8 hours at a time over 40 hours. And a crew of aunties brought trays of musubi, stew, sandwiches, and burgers—a different but no less essential kind of fuel for the firing.

Once the kiln had been blessed (we're a Zen temple, after all), we spent the first 12 hours or so only bringing the kiln up to 900 degrees. This allowed the heat to evenly permeate all three of the kiln's chambers. Then, continuing to use only the wood we had gathered, we raised the temperature over the next 24 hours to over 2400 degrees.

By the time the kiln was approaching full temperature, it was burning in what's called reduction, with more fuel on fire than there was oxygen to feed it. This meant that, each time the chamber doors were opened to drop in new wood, flames and black smoke would come shooting out. We all wore protective gear—welding masks and fireproof gloves—because by this point the kiln itself and the door handles were too hot to touch. The welding masks were like super strength sunglasses, allowing us to see inside the kiln's chambers, which would otherwise have been an indistinguishable scene of white hot heat. For reference, the surface of the sun is about 10,000 degrees Fahrenheit. At about a quarter of that temperature, everything inside the kiln just shimmers like honey and shouldn't be looked at with the naked eye.

Inside the first chamber.

It's hard to describe the intensity o

f working the firebox of a 2400-degree kiln. It goes without saying that it's hot, a dry heat that evaporates the sweat off your body before you even realize you've sweated. And yet, somehow, your body also acclimates. So much so that eventually, at any distance away from the kiln, you might actually feel chilly. Also, the lack of oxygen close to the kiln zaps your energy. You feel exhausted, like you just need to lie down. And yet, the kiln requires constant attention—to who's opening which chamber door, whether the temperature is dropping or climbing, where your next supply of wood is coming from, whether the firebox needs more wood or a chance to burn off what's already inside. It is all thoroughly enlivening. For a full day after we stopped firing and sealed the kiln to cool down, I couldn't close my eyes without seeing flames behind my eyelids, the memory of that effortless alertness straightening my spine.

Finally, four days later, when the kiln had dropped down to around 200 degrees, we opened it up. Out came piece after piece of ceramic, darkly burnished by the reductive, oxygen-depleted atmosphere inside the kiln. Several pieces were coated in wood ash. Most displayed the traits you look for in a wood firing: beautiful, unpredictable drips of glaze and liquified ash, with surprising flecks of color and texture.

Unloading the kiln was thrilling, if laborious. Disassembling the unmortared walls of bricks, which we had put in place after loading the kiln, was tedious and meticulous work. Several dozen stone shelves were removed along with the ceramics along with a lot of wadding, a mixture of alumina hydrate and kaolin that doesn't melt and which had been rolled into small balls and placed underneath each of several hundred pieces to prevent them from sticking to the shelves. The pieces were still so hot as they came out of the kiln that we all wore cotton and leather gloves, patiently carrying one piece at a time to the ceramics studio, where each was laid out according to where it had been inside the kiln.

Now, we have perhaps half of all of the ceramics that we'll sell at Chozen-ji's Annual Zen Art Show in November. But while the fundraising value of the ceramics is of course important, that's not why we fire the kiln. And no, the true purpose of the firing is not to make art, even transcendent Zen art.

We fire our kiln, with all of the preparation required and the risks entailed, because it's a crazy thing to do. It is a way to manufacture conditions approaching life and death but which, at the end of the day, don't really matter. The worst thing that could happen, of course, is somebody getting hurt. But other than that, the worst outcome would be losing a bunch of ceramics. And after all, that's essentially just dirt.

What matters is that firing the kiln is excellent training—training in discipline and calculations, to make piece after piece and chop log after log until the supply you have is just right. It's also training in leadership, to be able to manage dozens of people and changing conditions. To lead the firing, one has to understand how to distribute pieces within the kiln for the best airflow as well as manage people's energy and the fiery backdrafts shooting out of chamber doors.

For some, the firing was also a chance to push beyond what they thought were their limits. Exhausted and ready to go home, they found a new store of energy to push the kiln up and up to new heights. Yes, they strategically stoked fireboxes and raked coals, but at 2000 degrees, raising a fire is less about technique than it is about sheer determination and willpower.

Last week, I wrote in my first issue of DEAR ZEN, my new advice column, about how important it is to find spiritual training in our lives.

"When training becomes life and life becomes training," I wrote, "it's possible to see any challenge as a means for self development."

Martial arts and religion are good places to find this feeling of life as training. But more mundane—and yet also, crazy—things like firing a ceramics kiln can become a spiritual endeavor. Finding the training in our day-to-day, it's possible to build the perseverance and spiritual strength we need to face actual hard things we may face in our lives that carry real stakes—the death of a loved one, a company on the verge of collapse, political division, etc.

We can find the spiritual strength to not only do hard things, but to do them without feeling defeated—bummed out or weighed down by grief or self pity. We can find beauty and thrill in the laborious things, in the hard things, and in the things that we're not quite sure we can pull off but we're going to try to do anyway.

As my teacher Sayama Daian Roshi has said, training is hard because life is hard. And yet, the goal of hard training is to be free and happy. That is the ultimate transcendence—when the hardest things in life become vehicles for freedom and happiness. And therein, you'll find the essence of Zen.